New research from OSI and its Delaware River Watershed Initiative partners aims to quantify just how much forest protection is needed to ensure clean water.

It’s well known that forests filter the water that nourishes our families, supports businesses, and sustains our communities. Now, new research from the Open Space Institute (OSI) and its partners through the Delaware River Watershed Initiative aims to quantify just how much forest protection is needed to ensure clean water.

Thanks to an investment by the William Penn Foundation, OSI and its partners have been able to look back at the impact from past land protection. The research offers three novel approaches to gauge the benefits of forest protection and demonstrates the critical role forests play in filtering pollutants and maintaining high-quality streams for drinking water, recreation, and wildlife.

The three-year study led by OSI is part of the Delaware River Watershed Initiative, a four-state collaborative funded by William Penn Foundation to restore and protect the watershed that serves as the source of drinking water for 15 million people, including residents of New York City, Trenton, Philadelphia, and Wilmington.

See a larger version of the graphic here.

Working with the Initiative’s science leads — Stroud Water Research Center, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, and Shippensburg University — OSI assessed the water quality impact of 45 land protection projects funded through its Delaware River Watershed Protection Fund, spanning nearly 20,000 acres clustered across 21 priority sub-watersheds.

The research combines complementary scientific approaches, computer modeling, and stream sampling; together, these approaches offer perspective on how hypothetical scenarios change water quality, and actual data on where water quality begins to decline in specific forested headwaters.

The success of this approach lies in capturing a fuller story about the value of land protection. It builds upon OSI’s 2019 research, which shows that programs that fund land protection for water quality either skip evaluation altogether or use “avoided development” models — i.e., what would have happened had the land not been conserved — as the primary measure of success.

However, the issue with this approach is that most development models assume future development will follow existing patterns – creating a built-in bias that intact headwaters are at low risk of development, and therefore lower priority for investments in land protection. However, as the recent spike in demand for homes in rural markets spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic and growing acceptance of remote work underscores, this isn’t always the case.

To address existing modeling limitations, OSI and its partners have developed three approaches.

First, the project team used a unique method to quantify the development and resulting pollution that may have occurred without land protection. Rather than solely using a model that assumed future development would follow existing patterns, OSI gathered local knowledge from the organizations protecting the land to assess realistic development scenarios, considering real-life factors such as local zoning, market trends, landowner intent, site characteristics, and knowledge of competing purchase offers.

This revised model suggests that had these properties not been protected, almost a third — or over 6,000 of the 20,000 acres protected by OSI’s Fund — would have been negatively impacted by development. This development would have resulted in a 10 percent increase in impervious surface, among the most dangerous land uses for water quality protection, in nine of the 21 watersheds where land protection occurred. Science has shown that once a watershed reaches 10 percent impervious surface, water quality begins to measurably degrade.

Second, by further extrapolating the data, the models were able to estimate that the pollution resulting from hypothetical development would be detectable, in aggregate, 280 miles downstream of the projects. To put that in context, that’s most of the main stem of the 340-mile Delaware River. The distance downstream combines several factors about the watershed conditions, including the pollutant load from development surrounding the parcel, into one simple number. The more “intact” the watershed where the parcel is located, the farther downstream the pollutants from development on the protected parcel would be detected in water quality measurements. This analysis offers a novel way of demonstrating the value of land protection in intact headwaters as a strategy to maintain clean water downstream.

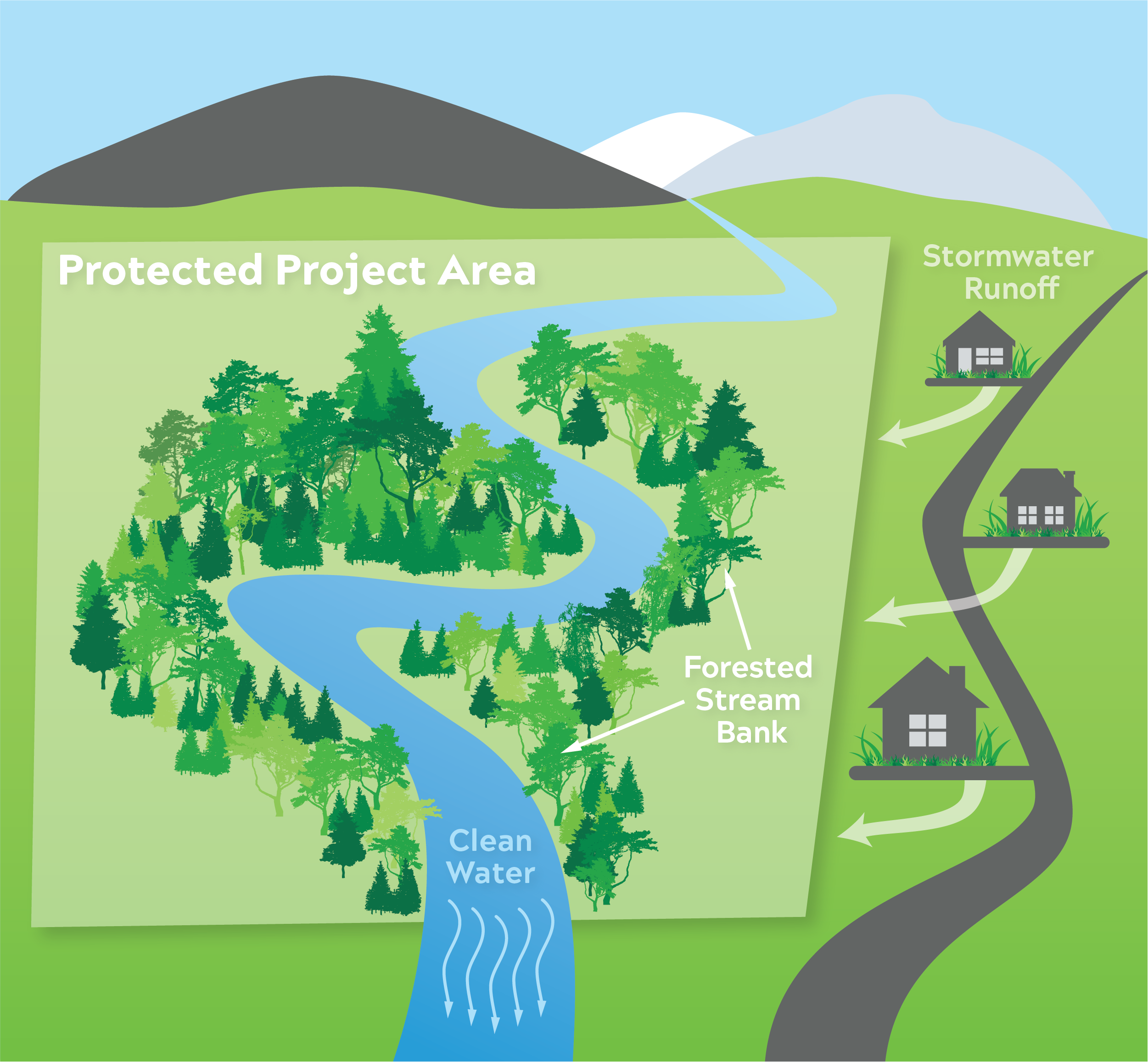

In a third approach, the team modeled how protected land can mitigate the water quality impact of pollutants from the local area surrounding the protected parcels. The forested streambanks on the 20,000 acres of land protected by OSI’s Delaware River Watershed Protection Fund serve to slow down the water and filter out pollutants coming from outside the parcel before they reach the stream.

The research finds that almost a third — or over 6,000 acres — of the 20,000 acres protected by OSI’s Delaware River Watershed Protection Fund would have been negatively impacted by development, had they not been protected by OSI.

To quantify just how much pollution is filtered, researchers mapped the land surrounding the OSI-funded land protection projects where stormwater runoff would eventually end up in the protected stream (the “watershed” of the protected stream). They then calculated the pollutants that rain would pick up from roads, farms and other development surrounding the parcel. As polluted rainwater runs off these lands, the protected forests capture and “treat” a subset of these pollutants before they reach the stream. In this way, the team calculated how many pounds of pollutants were diverted from the waterway thanks to the protective buffer of trees and vegetation along the streambank.

Across all projects, the forested stream banks diverted a total of 133,000 pounds of suspended solids and 185 pounds of phosphorus – the primary pollutants resulting in impairment to headwater streams – from 11,600 acres of land outside the project boundaries. This new approach helps to quantify the filtration ‘service’ provided by keeping the stream bank forested.

With the modeling component of the work wrapping up this winter, OSI is encouraged to see that results are telling a more complete story about the value of land protection for water quality. OSI and its partners are now working to answer another question: at what level of forest loss does water quality begin to decline in highly forested watersheds?

After a yearlong delay due to COVID-19, field crews from Stroud Water Research Center and the Academy of Natural Sciences commenced stream sampling work this past spring, collecting measurements at 51 sites across watershed in the upper Delaware Basin. This work will further inform the modeled results, explaining where water quality and indicators of stream health begin to be impacted by development.

The results of this stream sampling will help us quantify the “tipping point” for stream degradation — which is assumed to be 10 percent impervious surface within a given watershed but may be as low as three percent in the upper Delaware Basin.

Findings from this assessment will inform the work of the Initiative going forward and may even yield transferrable lessons for conservation funders, government entities, and other groups working to protect drinking water and stream health in other geographies.